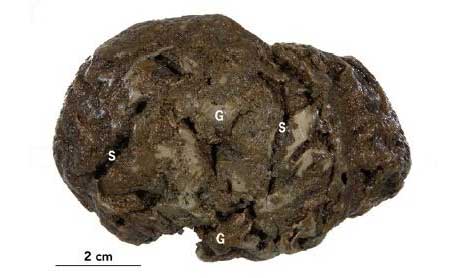

After death, soft tissue tends to decompose pretty quickly. The brain is soft tissue, so unless the tissue is mummified or preserved in some other way it doesn’t typically last long after death. That’s why this brain, exhumed from a grave in northwestern France in 1998, is so remarkable. The 18-month-old child it once belonged to died somewhere between 1250 and 1275 C.E., yet it is amazingly well preserved – so well preserved, in fact, that it contains remnants of neurons. The the circumstances surrounding the child’s death and the reason the brain is so well preserved are shrouded in mystery; CT and MRI scans didn’t bear out the initial theory that the child died from a cerebral hemorrhage, and the brain is this body’s only surviving soft tissue.

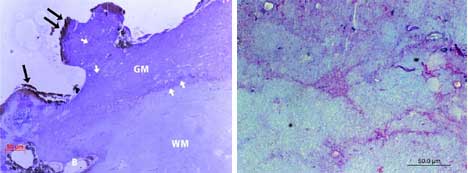

The child was laid to rest in a wood coffin, with its head wrapped in leather and placed on a pillow. The approximate date of death was determined by using tree-ring dating to determine the date the coffin was made. The child’s age was determined by its teeth. Beyond that, the details of the brain’s life and death seem murky. But since the brain is still one of the best-preserved medieval brains ever found, the University of Zurich team that’s examining it is very excited. Because of its good condition, the team have been able to perform far more tests on it than other specimens of similar age. Tissue samples showed grey matter and white matter (above, left) and pyramidal cells, which are a type of neuron (above, right). The very fact of the brain’s survival has led to new understanding of soft tissue decomposition. The complete study findings will be published in April 2010 in the journal NeuroImage.