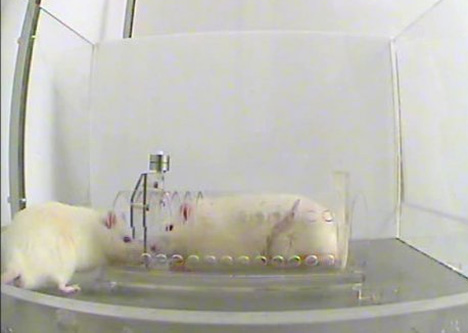

For many years, we humans have assumed that only “higher” primates could feel and express empathy. But a new experiment from the University of Chicago suggests that even rats feel the tug of kinship when they see a friend in trouble. The experiment centered on separating two rat “friends” who usually share a cage by locking one up in a small chamber. The other rat had the power to open the chamber and let the detainee out – and it surprisingly did so even when there was no reward involved.

The scientists tried a number of setups to identify exactly what was motivating the free rats to let their friends out of the restraint chamber. They removed any type of reward, including socialization with the other rat; they put empty restraint chambers in the cage to see if the rats were opening it just because they were curious about it. They even gave the free rat the choice between eating chocolate alone and freeing its friend. More than half of the time, the rat chose to open the restraint chamber and share the chocolate with its friend, suggesting the first real signs of rodent empathy and social behavior.

The rats weren’t trained before beginning the experiment, but they quickly learned several ways to open the restraint chamber door. In the initial runs of the experiment, both the free and restrained rats were startled by the opening door. In subsequent runs, they clearly knew how to achieve the result and did it on purpose. They seemed to understand exactly how to help their trapped friends and performed complex actions to do so, over and over.