Since the dawn of science fiction, the notion of suspended animation – human hibernation for long periods of time – has fascinated us. We’ve pictured using it to fly to distant worlds without aging, preserving our sickly bodies until a specific cure is invented, or even to deliver tiny, deceptively un-fun brine shrimp “pets” to unsuspecting children. It’s finally entering the realm of reality as surgeons at UPMC Presbyterian Hospital in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania prepare to save lives with a technique very similar to suspended animation.

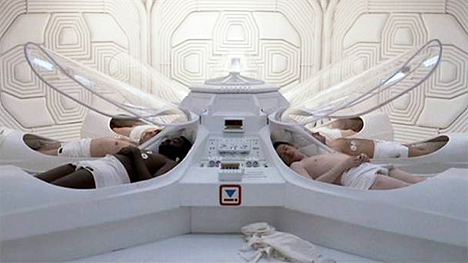

The team would prefer to call the technique “emergency preservation and resuscitation” since “suspended animation” suggests a sci-fi angle to the study and they’d like to preserve (pardon that pun) the seriousness of their study. The technique will be used on ten patients who come into the hospital with serious gunshot or knife wounds. By slowing – nearly stopping – cellular activity in the injured bodies via induced hypothermia, doctors may be able to buy themselves just enough time to fix the damage. The half alive/half dead condition is similar to the stasis into which space travelers are often placed in movies like Planet of the Apes and Alien to stop them from completing their human life cycle long before they reach their destination – but on a much smaller scale.

To accomplish this, doctors will replace all of a patient’s blood with a cooled saline solution. When the body temperature is rapidly decreased, chemical reactions in the body slow to a crawl and less oxygen is needed to keep the person alive. They are effectively held in a state between life and death. Putting an injured person into this state buys precious time for doctors to fix the damage to the body and save the patient’s life.

Animal trials began in 2002 and the results are very promising, but the real challenge is using the technique successfully on humans. The doctors are very selective about the type of patient they will test the procedure on – without the procedure, these patients would have less than a seven percent chance of survival. Pushing saline through the body will cool it rapidly, putting the patient into a state of clinical death. But actual death is staved off by the action of the induced hypothermia.

Under normal circumstances, cells need oxygen to survive and function. When someone with a normal body temperature is deprived of oxygen, cells can survive for about two minutes. Under induced hypothermia, that survival period extends up to two hours. The surgeons will use those two hours to repair interior damage and then replace the patient’s blood, slowly bringing them back to body temperature and back to life. The team involved in the study is cautiously optimistic, noting that we aren’t yet ready to send a space crew to Mars in stasis, but that if further trials go well they may be able to save people whose injuries would otherwise almost certainly prove fatal.